Facebook — From newspeak to newsroom

Much has been written about how the mass-penetration of Facebook has changed several of our most common conceptions in human relations, most centrally what Ethan J. Leib has called "the institution of friendship".

On February 3rd, Facebook will launch its new application, Paper. A new feature / application whose goal it is to make it easier for its users to "explore and share stories from friends and the world around [them]". The application is likely to deeply affect — once again — the virtual environment in which we evolve. As with every new innovation in this global playing field, there will be clear winners, and losers. Applications like news.me are not having a good day.

Marketing newspeak

On January 29th, I was privy to a small conference organized with Facebook's new Montreal bureau, whose representative Sylvain Martel described the (increasingly complex) mechanisms that underly the platform's success. In a short 40 minutes keynote, we discovered how intensely algorithmic the new laws of socialization have become. No one will be surprised to learn that, in the world of Facebook, "primetime is all the time." Despite some geographic disparities, the social network has massively penetrated nearly every country in the world. In September 2013, even China partly lifted its ban on the network.

In this spirit, Martel confirms that, while most of those who have been using the platform for some time have grown accustomed to its web-based interface, the company now sees itself as a mobile-first company, and will increasingly design future iterations accordingly. As we collectively engage in a Sisyphian quest of infinite scrolling, posts are now optimized to act as "thumbstoppers", that is, placeholders for restless fingers.

Rich content (not in the sense of more intellectual, but more 'multimedia'-oriented) takes the place of lesser forms (like text, or even audio), something we confirmed in interviews led with various producers over the past few weeks. In Facebook speak, what this means is that ADDvertising is replacing ADVERTising, a trend which content producers, agencies and end-users must consider as they develop their strategies.

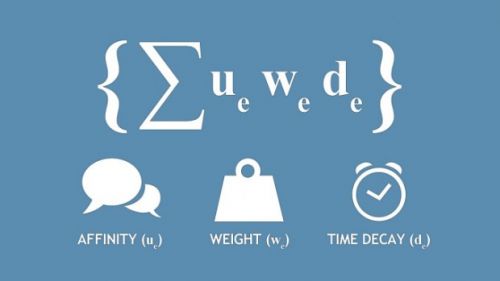

The importance of properly crafted marketing strategies on social media properties is nothing new, but the inertia that pages and identities carry with them changes the game significantly. Depending on a community's reactivity to page posts, Facebook attributes a "proximity score" to the page, which will in turn influence the number of people who will get to see any element of content organically. Pages that have had poor community management for a long time will find it difficult to ever generate engagement via Facebook, as they have not only to generate interesting posts, but also to move their (relatively inert) proximity score upwards.

For exemple, brands like Red Bull or Nike will be displayed naturally not only to a larger number of individuals (they have more fans than, say, f. & co), but also to a greater percentage of them. Why? Because for every post they make, the reactivity of their fans in inherently greater than with lesser properties who are not as focussed on a unitary brand message.

The war on (social) inertia

This has led companies such as Oreo and their agency (-of-the-year) 360i to build an actual "war room" around social media, a team which can consist of up to 15 or 20 people during peak times. The company rocketed to the top when, during the 2013 Superbowl blackout, it was able to produce a tweet that's now taught to every junior social media manager as a moment of pure bliss.

While the "Dunk in the Dark" story needs not be retold once again, the managerial dimension is worthy of our attention. As recounted by Ad Week's Christopher Heine, "the mere 11 minutes it took for the brand team to concoct a pitch-perfect and legally-approved message" was 18 months in the making.

Alas, Facebook has admitted to favouring "existing media properties" over other types of content producers. Thus, the ideas that stem from "public media", as they are known at Facebook, get more reach than other types of ideas. Hence established players in the media industry — from newspapers to television — will be favoured immensely in this new game of paperless papers.

What constitutes a "media" or, more specifically, whether smaller players can be deemed to produce elements of "public interest" remains to be seen. In a world where everybody is a media, and smaller entities (see our piece on Contributoria, or our series on the new economics of media) can produce investigative journalism often in quantity and quality unattainable by media conglomerates, Facebook will come to play a central role in the dynamics of democracy.

Let's hope that they take this "public" role as seriously as they have taken to transforming the institution of friendship, so that it doesn't act only as a promoter of the status quo dear to large conglomerates, but rather remains a driver of growth and opportunity for the small, emerging content creators of tomorrow.